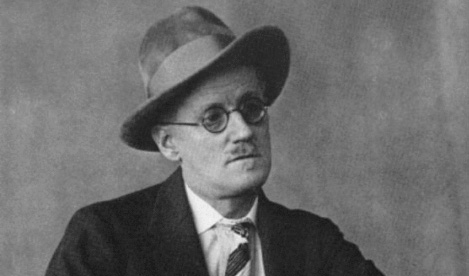

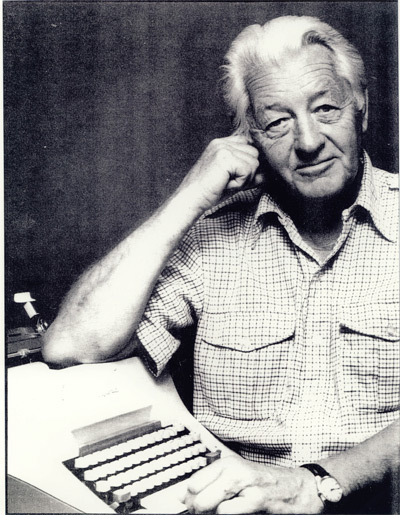

Impressions of the West: Wallace Stegner (Repost - March 1, 2011)

Monday, March 26, 2012 at 10:57PM Tweet

Monday, March 26, 2012 at 10:57PM Tweet  Photo courtesy of KUED.org

Photo courtesy of KUED.org

From The Sense of Place, by Wallace Stegner (1992):

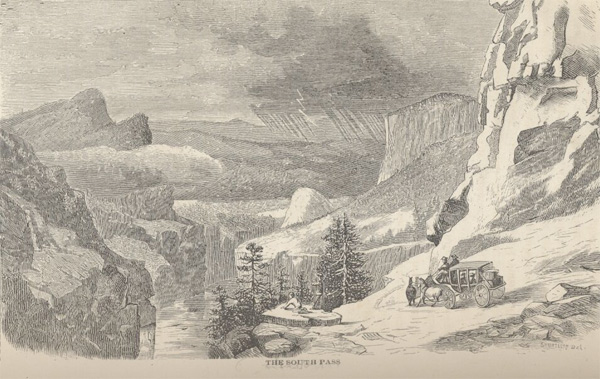

"Back to Wendell Berry, and his belief that if you don’t know where you are you don’t know who you are. He is not talking about the kind of location that can be determined by looking at a map or a street sign. He is talking about the kind of knowing that involves the senses, the memory, the history of a family or a tribe. He is talking about the knowledge of place that comes from working in it in all weathers, making a living from it, suffering from its catastrophes, loving its mornings or evenings or hot noons, valuing it for the profound investment of labor and feeling that you, your parents and grandparents, your all-but-unknown ancestors have put into it. He is talking about the knowing that poets specialize in.

It is only a step from his pronouncement to another: that no place is a place until it has had a poet.

No place, not even a wild place, is a place until it has had that human attention that at its highest reach we will call poetry. What Frost did for New Hampshire and Vermont, what Faulkner did for Mississippi and Steinbeck for the Salinas Valley, Wendell Berry is doing for his family corner of Kentucky, and hundreds of other place-loving people, gifted or not, are doing for places they were born in, or reared in, or have adopted and made their own…"