The Schopenhauer Reading Society

Sunday, January 15, 2012 at 3:08PM Tweet

Sunday, January 15, 2012 at 3:08PM Tweet By Jim Poulton

Credit: Utah Historical SocietyI come by my reading society bona fides honestly. I’m the proud member of two reading groups, both of which began in 1982. But that’s not all. Apparently, this obsession with reading is genetic. My great great aunt, if I can believe what my mother told me when I was a child, started the Schopenhauer Reading Society in Idaho Falls, Idaho in the 1880s or 1890s. My mother was proud of this aunt – proud that she’d been an intellectual in the early days of the state, and that she’d read books that didn’t make it on her religious community’s list of approved works. Even the title – the Schopenhauer Reading Society, named after the philosopher, professional curmudgeon and pessimist Arthur Schopenhauer – seemed to be a statement of my aunt’s independent spirit.

Credit: Utah Historical SocietyI come by my reading society bona fides honestly. I’m the proud member of two reading groups, both of which began in 1982. But that’s not all. Apparently, this obsession with reading is genetic. My great great aunt, if I can believe what my mother told me when I was a child, started the Schopenhauer Reading Society in Idaho Falls, Idaho in the 1880s or 1890s. My mother was proud of this aunt – proud that she’d been an intellectual in the early days of the state, and that she’d read books that didn’t make it on her religious community’s list of approved works. Even the title – the Schopenhauer Reading Society, named after the philosopher, professional curmudgeon and pessimist Arthur Schopenhauer – seemed to be a statement of my aunt’s independent spirit.

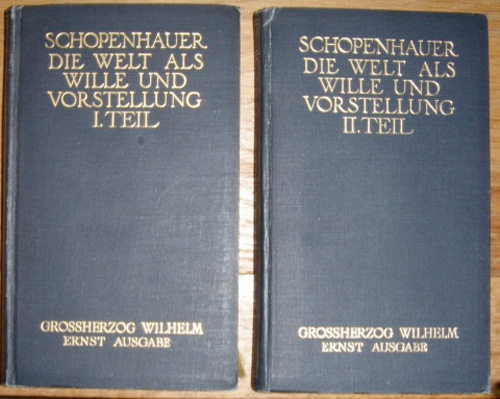

Schopenhauer’s Welt als Wille und Vorstellung. Credit: zvab.comI’ve asked through my family about this aunt, and no one knows anything about her. If she and the Schopenhauer Reading Society existed, they’re lost in the winds of time. But it got me wondering – how common were reading societies in the early West? And what was their purpose?

Schopenhauer’s Welt als Wille und Vorstellung. Credit: zvab.comI’ve asked through my family about this aunt, and no one knows anything about her. If she and the Schopenhauer Reading Society existed, they’re lost in the winds of time. But it got me wondering – how common were reading societies in the early West? And what was their purpose?

Here are a couple of examples.

Credit: Utah Historical SocietyIn Silvana, Washington, the Norsk Læse- og Samtaleforening (roughly the Norwegian Reading Society) was formed sometime around the mid 1800s. It was centered in the Norwegian Lutheran community, but its constitution could have been written by my iconoclastic aunt. “The society,” it said, “is not a religious society,” meaning they didn’t want the church telling them what to think or read. The purpose of the society was to promote the “profitable use of idle time” through “the purchase and reading of good books together with conversation.” In other words, as a group they bought books and passed them around among their members, so everyone could read them.

Credit: Utah Historical SocietyIn Silvana, Washington, the Norsk Læse- og Samtaleforening (roughly the Norwegian Reading Society) was formed sometime around the mid 1800s. It was centered in the Norwegian Lutheran community, but its constitution could have been written by my iconoclastic aunt. “The society,” it said, “is not a religious society,” meaning they didn’t want the church telling them what to think or read. The purpose of the society was to promote the “profitable use of idle time” through “the purchase and reading of good books together with conversation.” In other words, as a group they bought books and passed them around among their members, so everyone could read them.

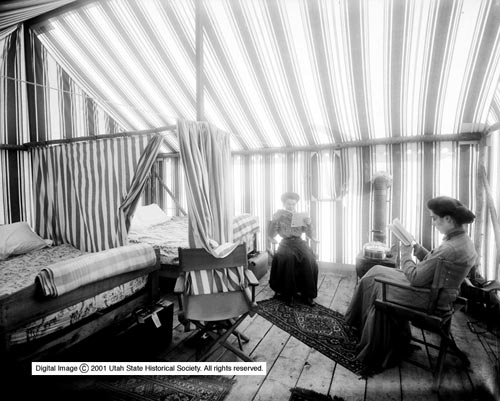

Miss Foster, faculty at Carlisle Indian School, full length, reclining in chair, reading a book, 1864. Credit: Library of CongressThis is one of the things I love about the history of the West. In the 1800s, the West was wild and wooly, as we all know. But a lot of people were also striving to use their minds as well as their muscles. A friend of mine told me once that a great great grandfather of his, who settled in Wyoming in the 1860s, paid big money to have philosophy books, written in German and French, brought to him on the Union Pacific train from New York.

Miss Foster, faculty at Carlisle Indian School, full length, reclining in chair, reading a book, 1864. Credit: Library of CongressThis is one of the things I love about the history of the West. In the 1800s, the West was wild and wooly, as we all know. But a lot of people were also striving to use their minds as well as their muscles. A friend of mine told me once that a great great grandfather of his, who settled in Wyoming in the 1860s, paid big money to have philosophy books, written in German and French, brought to him on the Union Pacific train from New York.

Here’s another example:

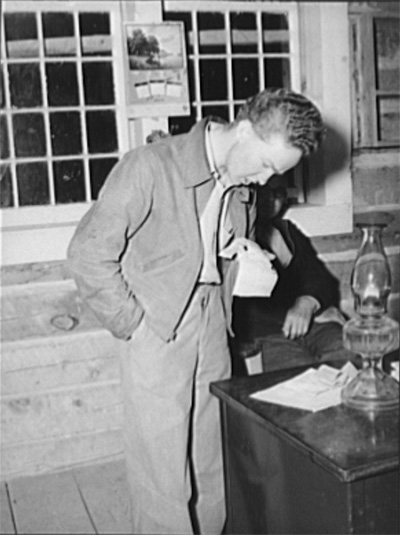

Farm boy reading jokes as his part of the program at the literary society meeting. Pie Town, New Mexico. Credit: Library of Congress. Circa 1940In February 1874, two young men in Salt Lake City were feeling pessimistic about their hopes of finding true romance. One of them, Jim Ferguson, “had heard, no doubt, of fond couples ‘reading life’s meaning in each others eyes,’” and suggested that they form an association of readers. A short while later, the Wasatch Literary Society was born. It wasn’t that unusual – even at that early date. As the journal BYU Studies says, ‘the 1870s were ripe for cultural societies’ in the Intermountain West, and by 1874, the early Mormon settlers had already fostered many cultural societies, including the ‘Polysophical,’ the ‘Philomathian,’ and the ‘Universal Scientific’ societies, all devoted to expanding the cultural literacy of their members.

Farm boy reading jokes as his part of the program at the literary society meeting. Pie Town, New Mexico. Credit: Library of Congress. Circa 1940In February 1874, two young men in Salt Lake City were feeling pessimistic about their hopes of finding true romance. One of them, Jim Ferguson, “had heard, no doubt, of fond couples ‘reading life’s meaning in each others eyes,’” and suggested that they form an association of readers. A short while later, the Wasatch Literary Society was born. It wasn’t that unusual – even at that early date. As the journal BYU Studies says, ‘the 1870s were ripe for cultural societies’ in the Intermountain West, and by 1874, the early Mormon settlers had already fostered many cultural societies, including the ‘Polysophical,’ the ‘Philomathian,’ and the ‘Universal Scientific’ societies, all devoted to expanding the cultural literacy of their members.

Homer Brown joined the Salt Lake Polysophical Society in December 1855. Credit: GatheringGardiners.Blogspot.comThe Wasatch Literary Society was relatively short-lived, and met its ignominious end in 1878. But while it was going, it drew some of the brightest lights of the young pioneers, and presumably Jim Ferguson and his friend finally found romance.

Homer Brown joined the Salt Lake Polysophical Society in December 1855. Credit: GatheringGardiners.Blogspot.comThe Wasatch Literary Society was relatively short-lived, and met its ignominious end in 1878. But while it was going, it drew some of the brightest lights of the young pioneers, and presumably Jim Ferguson and his friend finally found romance.

Emily Wells, early member of the Wasatch Reading Society. Credit: Growing Up Early in Utah

Emily Wells, early member of the Wasatch Reading Society. Credit: Growing Up Early in Utah

Credit: etsy.com

Credit: etsy.com